|

Base oil Selection – Beyond the Bench

Compoundings Magazine

February, 2001

By Thomas F. Glenn, Petroleum Trends International, Inc

Although mergers, acquisitions,

and exists have reduced the number of US base oil suppliers, the

number of options lubricant manufactures have to consider when formulating

finished lubricants has risen sharply. This is due primarily to

the emergence of Group II, II+ and III base oils over the last five

years. Blending is a much more complicated activity today than it

has been in the past and there is considerable room for success

and failure in the choices that are made.

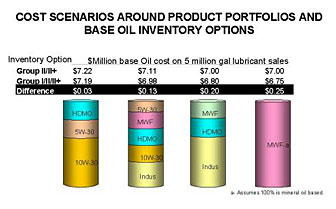

At one level, success and failure

will be measured by the impact base oil selection has directly on

the costs of good sold. A decision to use a typical Group I instead

of Group II to blend a 10W-30 passenger car motor oil (PCMO), for

example, can cost a manufacturer as much as $0.10 a gallon more

in total formulation costs for that product. This could be a very

costly mistake if 10W-30 PCMO is the primary product in the supplier’s

portfolio. The opposite could be true, however, if a blender uses

Group II to manufacture its industrial lubricants and only has a

small share of its business in PCMO. Although these examples may

present what appear to be obvious and relatively easy blending challenges

to resolve, they can get very complicated when one factors in other

considerations. These include differences in product portfolios,

supply line assurances, contract issues, tankage limitations, competitive

positioning, supply and blending logistics, and variation in base

oil quality, among others. As shown in Figure 1, base oil

costs can vary considerably if a blender does not optimized inventory

around product portfolios.

Base oil quality does vary even

within a given API Group and viscosity grade, and this variability

caninfluence total formulation costs. The aromatic content of a

heavy Group II, for example, can vary as much as 4 to 5% between

suppliers. Differences of several VI units between suppliers of

light and medium neutrals are also not unusual. For some, these

variations in VI open the doors for opportunistic ways to reduce

costs by backing out VI improver. For others, however, they could

result in cost burdens, or tradeoffs in volatility or low temperature

performance. Even greater differences in quality and impacts on

costs can be seen in the supply of Group I. In fact, some Group

I base oils are very near in quality to Group II, whereas others

have a long way to go.

Lubricant manufactures are now

challenged to optimize base oil costs and performance across product

lines with increasingly different appetites and thresholds of sensitivity

on price and performance. In some cases this process may require

a decision to install more base oil storage tanks. In others, it

may require forming a strategic alliance with another lubricant

manufacture in an effort to optimize costs through reciprocal manufacturing

agreements that allow each member of the alliance to focus on its

most profitable business segments. Still others may find the best

solution is to outsource manufacturing of a given product line,

or simply drop it all together.

These and other decisions go well

beyond simply the cost of goods sold for a given product in the

portfolio. Base oil selection will increasingly have strategic implications

that can result in long-term competitive advantages and disadvantages.

As a result, although formulation of lubricants at the bench top

is clearly best left in the hands of chemists and other professionals

with similar expertise,the probability of economic success beyond

the bench can be greatly increased if base oil selection is assessed

within the context of the company’s overall business strategy

and includes ongoing dialog with business managers, sales and marketing

and others in the organization.

Copyright © Petroleum Trends International,

Inc. 2002

|